Monday, March 31, 2008

Overload: Needing a RAM UPGRADE for ONE SLOT

(The Weekend Poem dedicated to a stressful week, weekend, and to challenging friendships!)

Live music Wednesday promises to dispel anxiety

Red curtains

Dim lights

“European connection” has panic attack

Recovers, and

Intergrates into the ‘crap’ band

Is the nauseauting Argentinian still speaking about himself?

FYI: Che Boludo, you've been tuned out!

($5.00 to hear Jai Lopez play, $6.00 for a glass of shiraz, and leaving your house in pj's is still stupid.)

And so it begins,

The faint sound of the conga accompanied by two acoustic guitars and the…

Pleasing, seductive sound of the curly-haired, Caribbean muse

with deep laugh/smile lines and deep, hypnotizing gaze

Whispers into the microphone, barely audible,

“and I want everything...."

Reggae solo

Delicious hug

Ah, delicious hug!!!

Stress induced hives

Fatiguing testosterone levels

Male friends blurring boundaries

Exhaustion from re-asserting boundaries

What is friendship anyway?

Tiredly,

Too many men and women with too many “needs” requiring too much attention

I am tired.

Can I please attempt to sleep?

Can you please call someone else?

The black, titanium American Express card

$900 on an ipod and ALL the relevant accessories

Getting yelled at by your wife for impulse shopping: priceless

"14 day return policy, 10% restocking fee..."

blah blah blah blah

"Why can't you spend your own money at Apple?"

Apple employee steal "my" digits

What is stalking anyway??

"You were talking to that customer for too long."

Disbelief sets in, "Wow, he is a pyscho!"

Need a new phone service anyway

HR webpage? What the hell is that?

Where are all the female friends?

At the bars and clubs (yawn),

And Cabo San Lucas (NICE!)

the yoga parties with the jacuzzi (yawn),

Baby Bake,

The View….

I,

at the politically charged film festival (YAWN!!!!)

How was the jacuzzi party?

Confused and worried

Oh, yes, back to male drama

(telenovela style)

Heart beating fast

Heart beating too fast

Heart beating too fast for too long!

Restful sleep out the window

Forgot to say, "thanks for that."

Solemn and worried faces of overindulgent parents

No words of consolation to offer them

Incredulous chain of events,

Illogical, irrational, emotionally charged

Clarification necessitated: Woman beater v. woman biter!

Why did you bite her?

A Day of Therapy: Weed-pulling Sunday

Or in Rio Platense, "chou chou"

Italians with high food and wine standards

Inspiration Hits: the tiramisu run….!

Boys fetch ingredients

(Men belong in the kitchen )

Weed pulling women

Amazing therapy in the yard

Faint sounds of jazz music

Tapas and conversation, anyone?

Banana nut bread G O N E

Cheese and wine run!

GIRLS fetch ingredients

Cherry cheese? (Yuck!)

Emmentaler never disappoints

SPICY Italian Salami

Everyone contemplates a bite

Dig in already

It's Sunday and we aren't arresting anyone today,

(Not as long as there is enough tiramisu to go around)

Bite Me!

Friday, March 28, 2008

Don't Miss the 4th Annual CINEMUJER Film Festival at the Esperanza Center

@ ESPERANZAPeace and Justice Center

922 San Pedro, San Antonio Texas 78212

(@ W Evergeen, 1/2 mile north of downtown)Call 210.228.0201 for more info.

http://www.esperanzacenter.org/

Thursday, March 6, 2008

A Little Story.

When I was in the third grade we were in 'Social Studies' class, or what I like to call, indoctrinization class. And we were studying about American Politics, i.e. how the President gets elected. I remember the students had to take turns reading the various paragraphs out loud. After all the reading was said and done I raised my hand and said,

"I don't understand this. Can you repeat it?"

The teacher asked, "Michelle, what don't you understand?"

I said," I don't understand how the President gets elected. First we talk about the definition of 'democracy' and then we talk about how the President gets elected. It makes no sense. Can you please explain it again?"

The teacher looked at me confused and robotically re-read the definition of 'democracy'.

So I raised my hand again and asked, "Okay, so if the President does not get elected by getting more votes how is that 'democracy'?"

Needless to say, the teacher NEVER answered my question. But instinctly I remember thinking and feeling like the system was stupid and broken and ..... didn't make any sense to me.

Our projections show the most likely outcome of yesterday's elections will be that Hillary Clinton gained 187 delegates, and we gained 183.

That's a net gain of 4 delegates out of more than 370 delegates available from all the states that voted.

For comparison, that's less than half our net gain of 9 delegates from the District of Columbia alone. It's also less than our net gain of 8 from Nebraska, or 12 from Washington State. And it's considerably less than our net gain of 33 delegates from Georgia.

The task for the Clinton campaign yesterday was clear. In order to have a plausible path to the nomination, they needed to score huge delegate victories and cut into our lead.

They failed.

It's clear, though, that Senator Clinton wants to continue an increasingly desperate, increasingly negative -- and increasingly expensive -- campaign to tear us down.

That's her decision. But it's not stopping John McCain, who clinched the Republican nomination last night, from going on the offensive. He's already made news attacking Barack, and that will only become more frequent in the coming days.

Right now, it's essential for every single supporter of Barack Obama to step up and help fight this two-front battle. In the face of attacks from Hillary Clinton and John McCain, we need to be ready to take them on.

Will you make an online donation of $25 right now?

http://my.barackobama.com/page/m/f6c10d702b7052c7/RjwGhA/VEsH/

The chatter among pundits may have gotten better for the Clinton campaign after last night, but by failing to cut into our lead, the math -- and their chances of winning -- got considerably worse.

Today, we still have a lead of more than 150 delegates, and there are only 611 pledged delegates left to win in the upcoming contests.

By a week from today, we will have competed in Wyoming and Mississippi. Two more states and 45 more delegates will be off the table.

But if Senator Clinton wants to continue this, let's show that we're ready.

Make an online donation of $25 now to show you're willing to fight for this:

http://my.barackobama.com/page/m/f6c10d702b7052c7/s0Hnub/VEsE/

This nomination process is an opportunity to decide what our party needs to stand for in this election.

We can either take on John McCain with a candidate who's already united Republicans and Independents against us, or we can do it with a campaign that's united Americans from all parties around a common purpose.

We can debate John McCain about who can clean up Washington by nominating a candidate who's taken more money from lobbyists than he has, or we can do it with a campaign that hasn't taken a dime of their money because we've been funded by you.

We can present the American people with a candidate who stood shoulder-to-shoulder with McCain on the worst foreign policy disaster of our generation, and agrees with him that George Bush deserves the benefit of the doubt on Iran, or we can nominate someone who opposed the war in Iraq from the beginning and will not support a march to war with Iran.

John McCain may have a long history of straight talk and independent thinking, but he has made the decision in this campaign to offer four more years of the very same policies that have failed us for the last eight.

We need a Democratic candidate who will present the starkest contrast to those failed policies of the past.

And that candidate is Barack Obama.

Please make a donation of $25 now:

http://my.barackobama.com/page/m/f6c10d702b7052c7/MUaiQO/VEsF/

Thank you,

David

David PlouffeCampaign Manager

Wednesday, March 5, 2008

Financial sinners won't have to wait for the afterlife to be punished for their various misdeeds. Plenty of consequences await in the here and now.

Presented with choices daily, human beings can lead chaste and charitable fiscal lives. Or they can succumb to fleeting temptations and fatal traps.

So choose to commit these deadly sins -- or work to bring a little temperance into your spending.

7 deadly debt sins:

Envy

The rich and famous luxury items are accessible now more than ever -- and without the wealth they once implied. With more and more people sporting expensive goods, it's easy to feel left out and far behind.

"The income disparity has gone up considerably, and what has happened is that it has changed our consumption patterns," says Ronald Wilcox, professor of business administration at the Darden School of Business, University of Virginia and author of the upcoming book, "Whatever Happened to Thrift? Why Americans Don't Save and What to Do about It."

Envy colors our perceptions. "What we decide is reasonable to consume is what we view being consumed around us," he says. "But because income disparities are so incredibly unequal, what we view around us really is beyond our ability to afford."

Consumers can get caught up trying to keep up with the Joneses or the upper-middle-class families they see on TV, believing they should own the same things others own.

"The problem with this scenario is that living like the rich doesn't last that long. And if you consider appearing in bankruptcy court as being famous, then you have achieved half your goal," says Terry Rigg, editor of Budget Stretcher, a Web site for the frugally minded.

Forget that pride goes before a fallPride can get in the way of preparing for worst-case scenarios.

People tend to feel overly optimistic about their ability to pay back debt, stay out of harm's way and maintain perfect vehicular performance indefinitely.

All human beings suffer from overconfidence -- but Americans more than anyone, says Ronald Wilcox, author of the upcoming book, "Whatever Happened to Thrift? Why Americans Don't Save and What to Do about It," and a professor of business administration at the University of Virginia.

"Our nation has seen great benefits from the confidence to take risks. Risk-taking built Manhattan. But there is a dark underbelly," he warns. "There are some winners and they do great things, but there are a lot of losers. And one of the risks that people take is spending all their money now and not saving for a rainy day."

Incredible though it may be, cars do sometimes need repairs, cavities need to be filled and surgeries may be required that insurance doesn't completely cover.

"We hear it all the time, but everyone has got to have an emergency fund. It's not if it happens, but when," says Gail Cunningham, senior director of public relations for the National Foundation for Credit Counseling.

Be slothful with financesFinances tend to be complicated and require some mental manipulation of the most dreaded of all things: numbers. Failure to pay attention to loan terms and due dates can have severe consequences.

A survey for Bankrate.com's Financial Literacy series last year revealed that 34 percent of homeowners had no idea what type of mortgage they had -- whether it had a fixed or adjustable rate.

"I like to use the term 'financial complacency' to describe people that never really take the time to get the big picture of their finances," says Terry Rigg, editor of Budget Stretcher Web site and newsletter.

We prefer the term "sloth."

Avoidance is easy; paying attention is hard, especially when confronted with unpleasant facts like a hefty credit card bill or struggling to learn something new like investing basics just to enroll in a company-sponsored retirement plan.

"Americans don't really understand parts of those plans," says Wilcox. "This is probably due in part to Americans' reduced interest in mathematics relative to the rest of the world. Americans don't study it as intensely and they don't really understand the benefits of compound interest."

Get greedy when borrowingWhy buy an economy car when you can get a loan for twice as much and ride around in style?

Over-buying (read: greed) is a trap into which consumers can easily stumble.

A dollar is not always a dollar in our minds, says Ronald Wilcox, professor of business administration at the University of Virginia and author of the upcoming book, "Whatever Happened to Thrift? Why Americans Don't Save and What to Do about It." Some days a dollar will be more valuable to you than others.

Often when making big purchases, the price seems so overwhelmingly high that smaller add-ons or upgrades start looking like great deals in comparison.

"What you're doing is pairing the smaller purchase with the bigger number and all of a sudden it looks reasonable in comparison when on any other day you would recognize this as a really bad deal," says Wilcox.

"Marketers are aware of that, so they will add on lots of small items -- like warranties for instance -- things that have huge margins that they can make a lot of money on," he says.

Rationalizations could include, "Well I'm already borrowing $10,000, so what's another $3,000?"

"Learn not to buy on impulse and plan every purchase carefully. If you don't have the money now -- save until you do," says Terry Rigg, editor of Budget Stretcher, a Web site and newsletter.

Feel wrathful at everyone but yourselfBlame others for your own financial missteps. That way you never have to learn anything new.

To the peril of individuals, lenders won't cut you off when you've had enough. Criminal nondisclosure of loan details aside, lenders aren't in the business of making sure you save money and don't overspend.

"The savings crisis and the household debt crisis are directly related to each other," says Ronald Wilcox, author of the upcoming book, "Whatever Happened to Thrift? Why Americans Don't Save and What to Do about It," and professor of business administration at the University of Virginia.

"We wouldn't see foreclosures go up as quickly if people had a cushion of savings."

So wrath, when targeting others, is often misdirected. Developing a strategy for your finances is a personal responsibility, says Wilcox.

"On the corporate side of things, companies can do things that can make it easier for people to figure out how to save and save in an effective way," says Wilcox. "And the same goes for the government. They can make it easier for people, but can't force anyone to do anything."

For instance, companies can automatically enroll their employees in their retirement plans, but participation in a savings plan can't be a condition of employment. Similarly, the government provides tax incentives for saving in retirement accounts such as IRAs, but you can't be thrown in jail for not taking advantage of it.

To avoid messy situations, develop a budget with both savings and debt pay-down strategies -- and stick to it.

"It's much easier to tell yourself and your kids 'no' if you know what the spending limits are. Everyone in the family should know that they can't get everything they want because the money is just not there," says Terry Rigg, editor of Budget Stretcher, a Web site and newsletter.

Be gluttonousYou deserve that cookie so go ahead and eat it and maybe a couple more for good measure. While you're at it, buy the bedroom set you can't afford but deeply desire.

As a nation, the United States is both plainly fat from eating too much and overstuffed in the materialistic sense. The message from society in general can sometimes be: You work hard, so splurge.

It's very possible to have a house full of stuff and no money. It's also possible to be extremely overweight and ingest no healthy nutrients.

Just like eating food for no good reason other than the fact that it is set in front of you, people buy stuff just to buy it.

"It's so easy when you're in a mall to start buying things on impulse. They're very attractive and all shiny and new -- especially when they're on sale," says Dave Jones, president of the Association of Independent Consumer Credit Counseling Agencies.

"People will react to a sale item -- 60 percent off -- and buy it when they don't need it or want it."

Big-box stores are vast dens of temptation, offering lots of everything at sale prices.

"People buy huge amounts of stuff and think they're saving money. But what happens is that it just takes up space, takes years to use up or it just spoils," Jones says. Let lust lead you into spendingWhat can a little coveting hurt if no action is taken?

Lust can take many forms. Stereotypical but true, it would be hard to find more than a handful of women who hadn't longed for a particularly fetching pair of shoes or other frippery on occasion.

As for men, one need look no further than the swimsuit edition of a popular sports magazine or the covers of various lad mags and other even more risqué publications that grace the newsstands.

That particular facet of lust was so vexing in centuries past that it was widely believed the afflicted would suffer greatly in the afterlife.

That facet of lust often does contribute to debt -- a contemporary hell -- in the modern day.

"Pornography is a very large industry, but it is hidden," says Stuart Vyse, author of "Going Broke: Why Americans Can't Hold on to Their Money."

"The fact that it is hidden makes it hugely popular because you can engage in it without anybody knowing."

And the Internet has made it very easy for people to indulge with little immediate consequence.

According to Vyse, it's estimated that Americans spend between $10 billion and $13 billion on adult entertainment.

That's a lot of money that might be put to better use in retirement accounts across the country.

Copyrighted, Bankrate.com. All rights reserved.

Tuesday, March 4, 2008

Rock Concert??

After standing in the scorching sun for two hours with my aging mother and handicapped brother, we were finally searched (pat down style) and allowed to sit in an auditorium for another hour and 15 minutes before Hillary Clinton spoke for about 30 minutes.

Question: Would I ever wait in line for that long to see another politician?

Answer: Probably not, but I would do it for a live music performer.

Last Friday Barack Obama, Bill Clinton and Senator John McCain were all in SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS trying to get more votes!!! Who would have thought this south Texas town would make it into the spotlight other than because of the SPURS winning the NBA Championship. I, however, decided that I would go see non one speak -- did not require sunscreen or Gatorade. I decided I would much rather go salsa dancing.

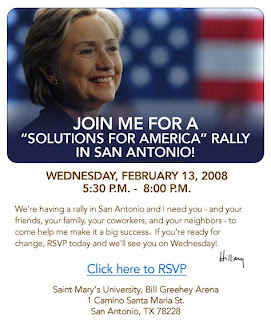

Monday, February 11, 2008

Thursday, January 24, 2008

Stillness. Church. Eternal Life????

I felt this profound irritation at being there and having to be told that I would be compensated for this life at a later date, at some point in time after my physical death in the "Eternal Life", in the "Forever and Ever and Ever", in the "Everlasting". The sermon was simplistic, meant to appease a misbehaving toddler, nothing profound or deep about it at all.

I have delved into Buddhism, reading as much as I can about it and trying to set aside my ego to truly understand my place in this cycle. Buddhism is not for the fainthearted. Buddhism asks you to live in this world, accept your place in this cycle, accept that everything is impermanent, and understand that you cannot fight change. No, Buddhism is definitely not for everyone, it is hard to understand, live, and foremost, very cerebral, but fills me. The answers don't come quickly nor easily, but when they come they don't just appease, they fill.

Buddhism is also the only religion that does not purport to be the only way, the right way, the only route to "salvation", or the only portal to heaven, i.e. the everlasting life, eternal life, forever and ever. It is the only religion that does not believe that everyone that does not believe in it (the members only club) is going to burn in hell like in Christianity, Judaism, or Islam. It doesn't feel juvenile, simplistic, or it doesn't feel like believing in the tooth ferry or in Santa Claus. It cuts deep into the human value system. Value meaning what Y O U value, as opposed to what one has been socialised to beliveve one should value, value being a relative, ever changing term.

Thursday, November 8, 2007

Christine Rosen: "Virtual Friendship and the New Narcissism"

On Thursday, October 4, Christine Rosen discussed this article on National Public Radio. Washington Post columnist Michael Gerson discussed this article in his column on October 5, 2007.

For centuries, the rich and the powerful documented their existence and their status through painted portraits. A marker of wealth and a bid for immortality, portraits offer intriguing hints about the daily life of their subjects—professions, ambitions, attitudes, and, most importantly, social standing. Such portraits, as German art historian Hans Belting has argued, can be understood as "painted anthropology," with much to teach us, both intentionally and unintentionally, about the culture in which they were created.

Self-portraits can be especially instructive. By showing the artist both as he sees his true self and as he wishes to be seen, self-portraits can at once expose and obscure, clarify and distort. They offer opportunities for both self-expression and self-seeking. They can display egotism and modesty, self-aggrandizement and self-mockery.

Today, our self-portraits are democratic and digital; they are crafted from pixels rather than paints. On social networking websites like MySpace and Facebook, our modern self-portraits feature background music, carefully manipulated photographs, stream-of-consciousness musings, and lists of our hobbies and friends. They are interactive, inviting viewers not merely to look at, but also to respond to, the life portrayed online. We create them to find friendship, love, and that ambiguous modern thing called connection. Like painters constantly retouching their work, we alter, update, and tweak our online self-portraits; but as digital objects they are far more ephemeral than oil on canvas. Vital statistics, glimpses of bare flesh, lists of favorite bands and favorite poems all clamor for our attention—and it is the timeless human desire for attention that emerges as the dominant theme of these vast virtual galleries.

Although social networking sites are in their infancy, we are seeing their impact culturally: in language (where to friend is now a verb), in politics (where it is de rigueur for presidential aspirants to catalogue their virtues on MySpace), and on college campuses (where not using Facebook can be a social handicap). But we are only beginning to come to grips with the consequences of our use of these sites: for friendship, and for our notions of privacy, authenticity, community, and identity. As with any new technological advance, we must consider what type of behavior online social networking encourages. Does this technology, with its constant demands to collect (friends and status), and perform (by marketing ourselves), in some ways undermine our ability to attain what it promises—a surer sense of who we are and where we belong? The Delphic oracle's guidance was know thyself. Today, in the world of online social networks, the oracle's advice might be show thyself.

Making Connections

The earliest online social networks were arguably the Bulletin Board Systems of the 1980s that let users post public messages, send and receive private messages, play games, and exchange software. Some of those BBSs, like The WELL (Whole Earth 'Lectronic Link) that technologist Larry Brilliant and futurist Stewart Brand started in 1985, made the transition to the World Wide Web in the mid-1990s. (Now owned by Salon.com, The WELL boasts that it was "the primordial ooze where the online community movement was born.") Other websites for community and connection emerged in the 1990s, including Classmates.com (1995), where users register by high school and year of graduation; Company of Friends, a business-oriented site founded in 1997; and Epinions, founded in 1999 to allow users to give their opinions about various consumer products.

A new generation of social networking websites appeared in 2002 with the launch of Friendster, whose founder, Jonathan Abrams, admitted that his main motivation for creating the site was to meet attractive women. Unlike previous online communities, which brought together anonymous strangers with shared interests, Friendster uses a model of social networking known as the "Circle of Friends" (developed by British computer scientist Jonathan Bishop), in which users invite friends and acquaintances—that is, people they already know and like—to join their network.

Friendster was an immediate success, with millions of registered users by mid-2003. But technological glitches and poor management at the company allowed a new social networking site, MySpace, launched in 2003, quickly to surpass it. Originally started by musicians, MySpace has become a major venue for sharing music as well as videos and photos. It is now the behemoth of online social networking, with over 100 million registered users. Connection has become big business: In 2005, Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation bought MySpace for $580 million.

Besides MySpace and Friendster, the best-known social networking site is Facebook, launched in 2004. Originally restricted to college students, Facebook—which takes its name from the small photo albums that colleges once gave to incoming freshmen and faculty to help them cope with meeting so many new people—soon extended membership to high schoolers and is now open to anyone. Still, it is most popular among college students and recent college graduates, many of whom use the site as their primary method of communicating with one another. Millions of college students check their Facebook pages several times every day and spend hours sending and receiving messages, making appointments, getting updates on their friends' activities, and learning about people they might recently have met or heard about.

There are dozens of other social networking sites, including Orkut, Bebo, and Yahoo 360º. Microsoft recently announced its own plans for a social networking site called Wallop; the company boasts that the site will offer "an entirely new way for consumers to express their individuality online." (It is noteworthy that Microsoft refers to social networkers as "consumers" rather than merely "users" or, say, "people.") Niche social networking sites are also flourishing: there are sites offering forums and fellowship for photographers, music lovers, and sports fans. There are professional networking sites, such as LinkedIn, that keep people connected with present and former colleagues and other business acquaintances. There are sites specifically for younger children, such as Club Penguin, which lets kids pretend to be chubby, colored penguins who waddle around chatting, playing games, earning virtual money, and buying virtual clothes. Other niche social networking sites connect like-minded self-improvers; the site 43things.com encourages people to share their personal goals. Click on "watch less TV," one of the goals listed on the site, and you can see the profiles of the 1,300 other people in the network who want to do the same thing. And for people who want to join a social network but don't know which niche site is right for them, there are sites that help users locate the proper online social networking community for their particular (or peculiar) interests.

Social networking sites are also fertile ground for those who make it their lives' work to get your attention—namely, spammers, marketers, and politicians. Incidents of spamming and spyware on MySpace and other social networking sites are legion. Legitimate advertisers such as record labels and film studios have also set up pages for their products. In some cases, fictional characters from books and movies are given their own official MySpace pages. Some sports mascots and brand icons have them, too. Procter & Gamble has a Crest toothpaste page on MySpace featuring a sultry-looking model called "Miss Irresistible." As of this summer, she had about 50,000 users linked as friends, whom she urged to "spice it up by sending a naughty (or nice) e-card." The e-cards are emblazoned with Crest or Scope logos, of course, and include messages such as "I wanna get fresh with you" or "Pucker up baby—I'm getting fresh." A P& G marketing officer recently told the Wall Street Journal that from a business perspective, social networking sites are "going to be one giant living dynamic learning experience about consumers."

As for politicians, with the presidential primary season now underway, candidates have embraced a no-website-left-behind policy. Senator Hillary Clinton has official pages on social networking sites MySpace, Flickr, LiveJournal, Facebook, Friendster, and Orkut. As of July 1, 2007, she had a mere 52,472 friends on MySpace (a bit more than Miss Irresistible); her Democratic rival Senator Barack Obama had an impressive 128,859. Former Senator John Edwards has profiles on twenty-three different sites. Republican contenders for the White House are poorer social networkers than their Democratic counterparts; as of this writing, none of the GOP candidates has as many MySpace friends as Hillary, and some of the leading Republican candidates have no social networking presence at all.

Despite the increasingly diverse range of social networking sites, the most popular sites share certain features. On MySpace and Facebook, for example, the process of setting up one's online identity is relatively simple: Provide your name, address, e-mail address, and a few other pieces of information and you're up and running and ready to create your online persona. MySpace includes a section, "About Me," where you can post your name, age, where you live, and other personal details such as your zodiac sign, religion, sexual orientation, and relationship status. There is also a "Who I'd Like to Meet" section, which on most MySpace profiles is filled with images of celebrities. Users can also list their favorite music, movies, and television shows, as well as their personal heroes; MySpace users can also blog on their pages. A user "friends" people—that is, invites them by e-mail to appear on the user's "Friend Space," where they are listed, linked, and ranked. Below the Friends space is a Comments section where friends can post notes. MySpace allows users to personalize their pages by uploading images and music and videos; indeed, one of the defining features of most MySpace pages is the ubiquity of visual and audio clutter. With silly, hyper flashing graphics in neon colors and clip-art style images of kittens and cartoons, MySpace pages often resemble an overdecorated high school yearbook.

By contrast, Facebook limits what its users can do to their profiles. Besides general personal information, Facebook users have a "Wall" where people can leave them brief notes, as well as a Messages feature that functions like an in-house Facebook e-mail account. You list your friends on Facebook as well, but in general, unlike MySpace friends, which are often complete strangers (or spammers) Facebook friends tend to be part of one's offline social circle. (This might change, however, now that Facebook has opened its site to anyone rather than restricting it to college and high school students.) Facebook (and MySpace) allow users to form groups based on mutual interests. Facebook users can also send "pokes" to friends; these little digital nudges are meant to let someone know you are thinking about him or her. But they can also be interpreted as not-so-subtle come-ons; one Facebook group with over 200,000 members is called "Enough with the Poking, Let's Just Have Sex."

Degrees of Separation

It is worth pausing for a moment to reflect on the curious use of the word networking to describe this new form of human interaction. Social networking websites "connect" users with a network—literally, a computer network. But the verb to network has long been used to describe an act of intentional social connecting, especially for professionals seeking career-boosting contacts. When the word first came into circulation in the 1970s, computer networks were rare and mysterious. Back then, "network" usually referred to television. But social scientists were already using the notion of networks and nodes to map out human relations and calculate just how closely we are connected.

In 1967, Harvard sociologist and psychologist Stanley Milgram, best known for his earlier Yale experiments on obedience to authority, published the results of a study about social connection that he called the "small world experiment." "Given any two people in the world, person X and person Z," he asked, "how many intermediate acquaintance links are needed before X and Z are connected?" Milgram's research, which involved sending out a kind of chain letter and tracing its journey to a particular target person, yielded an average number of 5.5 connections. The idea that we are all connected by "six degrees of separation" (a phrase later popularized by playwright John Guare) is now conventional wisdom.

But is it true? Duncan J. Watts, a professor at Columbia University and author of Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age, has embarked on a new small world project to test Milgram's theory. Similar in spirit to Milgram's work, it relies on e-mail to determine whether "any two people in the world can be connected via 'six degrees of separation.'" Unlike Milgram's experiment, which was restricted to the United States, Watts's project is global; as he and his colleagues reported in Science, "Targets included a professor at an Ivy League university, an archival inspector in Estonia, a technology consultant in India, a policeman in Australia, and a veterinarian in the Norwegian army." Their early results suggest that Milgram might have been right: messages reached their targets in five to seven steps, on average. Other social networking theorists are equally optimistic about the smallness of our wireless world. In Linked: The New Science of Networks, Albert-László Barabási enthuses, "The world is shrinking because social links that would have died out a hundred years ago are kept alive and can be easily activated. The number of social links an individual can actively maintain has increased dramatically, bringing down the degrees of separation. Milgram estimated six," Barabási writes. "We could be much closer these days to three."

What kind of "links" are these? In a 1973 essay, "The Strength of Weak Ties," sociologist Mark Granovetter argued that weaker relationships, such as those we form with colleagues at work or minor acquaintances, were more useful in spreading certain kinds of information than networks of close friends and family. Watts found a similar phenomenon in his online small world experiment: weak ties (largely professional ones) were more useful than strong ties for locating far-flung individuals, for example.

Today's online social networks are congeries of mostly weak ties—no one who lists thousands of "friends" on MySpace thinks of those people in the same way as he does his flesh-and-blood acquaintances, for example. It is surely no coincidence, then, that the activities social networking sites promote are precisely the ones weak ties foster, like rumor-mongering, gossip, finding people, and tracking the ever-shifting movements of popular culture and fad. If this is our small world, it is one that gives its greatest attention to small things.

Even more intriguing than the actual results of Milgram's small world experiment—our supposed closeness to each other—was the swiftness and credulity of the public in embracing those results. But as psychologist Judith Kleinfeld found when she delved into Milgram's research (much of which was methodologically flawed and never adequately replicated), entrenched barriers of race and social class undermine the idea that we live in a small world. Computer networks have not removed those barriers. As Watts and his colleagues conceded in describing their own digital small world experiment, "more than half of all participants resided in North America and were middle class, professional, college educated, and Christian."

Nevertheless, our need to believe in the possibility of a small world and in the power of connection is strong, as evidenced by the popularity and proliferation of contemporary online social networks. Perhaps the question we should be asking isn't how closely are we connected, but rather what kinds of communities and friendships are we creating?

Won't You Be My Digital Neighbor?

According to a survey recently conducted by the Pew Internet and American Life Project, more than half of all Americans between the ages of twelve and seventeen use some online social networking site. Indeed, media coverage of social networking sites usually describes them as vast teenage playgrounds—or wastelands, depending on one's perspective. Central to this narrative is a nearly unbridgeable generational divide, with tech-savvy youngsters redefining friendship while their doddering elders look on with bafflement and increasing anxiety. This seems anecdotally correct; I can't count how many times I have mentioned social networking websites to someone over the age of forty and received the reply, "Oh yes, I've heard about that MyFace! All the kids are doing that these days. Very interesting!"

Numerous articles have chronicled adults' attempts to navigate the world of social networking, such as the recent New York Times essay in which columnist Michelle Slatalla described the incredible embarrassment she caused her teenage daughter when she joined Facebook: "everyone in the whole world thinks its super creepy when adults have facebooks," her daughter instant-messaged her. "unfriend paige right now. im serious.... i will be soo mad if you dont unfriend paige right now. actually." In fact, social networking sites are not only for the young. More than half of the visitors to MySpace claim to be over the age of 35. And now that the first generation of college Facebook users have graduated, and the site is open to all, more than half of Facebook users are no longer students. What's more, the proliferation of niche social networking sites, including those aimed at adults, suggests that it is not only teenagers who will nurture relationships in virtual space for the foreseeable future.

What characterizes these online communities in which an increasing number of us are spending our time? Social networking sites have a peculiar psychogeography. As researchers at the Pew project have noted, the proto-social networking sites of a decade ago used metaphors of place to organize their members: people were linked through virtual cities, communities, and homepages. In 1997, GeoCities boasted thirty virtual "neighborhoods" in which "homesteaders" or "GeoCitizens" could gather—"Heartland" for family and parenting tips, "SouthBeach" for socializing, "Vienna" for classical music aficionados, "Broadway" for theater buffs, and so on. By contrast, today's social networking sites organize themselves around metaphors of the person, with individual profiles that list hobbies and interests. As a result, one's entrée into this world generally isn't through a virtual neighborhood or community but through the revelation of personal information. And unlike a neighborhood, where one usually has a general knowledge of others who live in the area, social networking sites are gatherings of deracinated individuals, none of whose personal boastings and musings are necessarily trustworthy. Here, the old arbiters of community—geographic location, family, role, or occupation—have little effect on relationships.

Also, in the offline world, communities typically are responsible for enforcing norms of privacy and general etiquette. In the online world, which is unfettered by the boundaries of real-world communities, new etiquette challenges abound. For example, what do you do with a "friend" who posts inappropriate comments on your Wall? What recourse do you have if someone posts an embarrassing picture of you on his MySpace page? What happens when a friend breaks up with someone—do you defriend the ex? If someone "friends" you and you don't accept the overture, how serious a rejection is it? Some of these scenarios can be resolved with split-second snap judgments; others can provoke days of agonizing.

Enthusiasts of social networking argue that these sites are not merely entertaining; they also edify by teaching users about the rules of social space. As Danah Boyd, a graduate student studying social networks at the University of California, Berkeley, told the authors of MySpace Unraveled, social networking promotes "informal learning.... It's where you learn social norms, rules, how to interact with others, narrative, personal and group history, and media literacy." This is more a hopeful assertion than a proven fact, however. The question that isn't asked is how the technology itself—the way it encourages us to present ourselves and interact—limits or imposes on that process of informal learning. All communities expect their members to internalize certain norms. Even individuals in the transient communities that form in public spaces obey these rules, for the most part; for example, patrons of libraries are expected to keep noise to a minimum. New technologies are challenging such norms—cell phones ring during church sermons; blaring televisions in doctors' waiting rooms make it difficult to talk quietly—and new norms must develop to replace the old. What cues are young, avid social networkers learning about social space? What unspoken rules and communal norms have the millions of participants in these online social networks internalized, and how have these new norms influenced their behavior in the offline world?

Social rules and norms are not merely the strait-laced conceits of a bygone era; they serve a protective function. I know a young woman—attractive, intelligent, and well-spoken—who, like many other people in their twenties, joined Facebook as a college student when it launched. When she and her boyfriend got engaged, they both updated their relationship status to "Engaged" on their profiles and friends posted congratulatory messages on her Wall.

But then they broke off the engagement. And a funny thing happened. Although she had already told a few friends and family members that the relationship was over, her ex decided to make it official in a very twenty-first century way: he changed his status on his profile from "Engaged" to "Single." Facebook immediately sent out a feed to every one of their mutual "friends" announcing the news, "Mr. X and Ms. Y are no longer in a relationship," complete with an icon of a broken heart. When I asked the young woman how she felt about this, she said that although she assumed her friends and acquaintances would eventually hear the news, there was something disconcerting about the fact that everyone found out about it instantaneously; and since the message came from Facebook, rather than in a face-to-face exchange initiated by her, it was devoid of context—save for a helpful notation of the time and that tacky little heart.

Indecent Exposure

Enthusiasts praise social networking for presenting chances for identity-play; they see opportunities for all of us to be little Van Goghs and Warhols, rendering quixotic and ever-changing versions of ourselves for others to enjoy. Instead of a palette of oils, we can employ services such as PimpMySpace.org, which offers "layouts, graphics, background, and more!" to gussy up an online presentation of self, albeit in a decidedly raunchy fashion: Among the most popular graphics used by PimpMySpace clients on a given day in June 2007 were short video clips of two women kissing and another of a man and an obese woman having sex; a picture of a gleaming pink handgun; and an image of the cartoon character SpongeBob SquarePants, looking alarmed and uttering a profanity.

This kind of coarseness and vulgarity is commonplace on social networking sites for a reason: it's an easy way to set oneself apart. Pharaohs and kings once celebrated themselves by erecting towering statues or, like the emperor Augustus, placing their own visages on coins. But now, as the insightful technology observer Jaron Lanier has written, "Since there are only a few archetypes, ideals, or icons to strive for in comparison to the vastness of instances of everything online, quirks and idiosyncrasies stand out better than grandeur in this new domain. I imagine Augustus' MySpace page would have pictured him picking his nose." And he wouldn't be alone. Indeed, this is one of the characteristics of MySpace most striking to anyone who spends a few hours trolling its millions of pages: it is an overwhelmingly dull sea of monotonous uniqueness, of conventional individuality, of distinctive sameness.

The world of online social networking is practically homogenous in one other sense, however diverse it might at first appear: its users are committed to self-exposure. The creation and conspicuous consumption of intimate details and images of one's own and others' lives is the main activity in the online social networking world. There is no room for reticence; there is only revelation. Quickly peruse a profile and you know more about a potential acquaintance in a moment than you might have learned about a flesh-and-blood friend in a month. As one college student recently described to the New York Times Magazine: "You might run into someone at a party, and then you Facebook them: what are their interests? Are they crazy-religious, is their favorite quote from the Bible? Everyone takes great pains over presenting themselves. It's like an embodiment of your personality."

It seems that in our headlong rush to join social networking sites, many of us give up one of the Internet's supposed charms: the promise of anonymity. As Michael Kinsley noted in Slate, in order to "stake their claims as unique individuals," users enumerate personal information: "Here is a list of my friends. Here are all the CDs in my collection. Here is a picture of my dog." Kinsley is not impressed; he judges these sites "vast celebrations of solipsism."

Social networkers, particularly younger users, are often naïve or ill-informed about the amount of information they are making publicly available. "One cannot help but marvel at the amount, detail, and nature of the personal information some users provide, and ponder how informed this information sharing can be," Carnegie Mellon researchers Alessandro Acquisti and Ralph Gross wrote in 2006. In a survey of Facebook users at their university, Acquisti and Gross "detected little or no relation between participants' reported privacy attitudes and their likelihood" of publishing personal information online. Even among the students in the survey who claimed to be most concerned about their privacy—the ones who worried about "the scenario in which a stranger knew their schedule of classes and where they lived"—about 40 percent provided their class schedule on Facebook, about 22 percent put their address on Facebook, and almost 16 percent published both.

This kind of carelessness has provided fodder for many sensationalist news stories. To cite just one: In 2006, NBC's Dateline featured a police officer posing as a 19-year-old boy who was new in town. Although not grounded in any particular local community, the imposter quickly gathered more than 100 friends for his MySpace profile and began corresponding with several teenage girls. Although the girls claimed to be careful about the kind of information they posted online, when Dateline revealed that their new friend was actually an adult male who had figured out their names and where they lived, they were surprised. The danger posed by strangers who use social networking sites to prey on children is real; there have been several such cases. This danger was highlighted in July 2007 when MySpace booted from its system 29,000 sex offenders who had signed up for memberships using their real names. There is no way of knowing how many sex offenders have MySpace accounts registered under fake names.

There are also professional risks to putting too much information on social networking sites, just as for several years there have been career risks associated with personal homepages and blogs. A survey conducted in 2006 by researchers at the University of Dayton found that "40 percent of employers say they would consider the Facebook profile of a potential employee as part of their hiring decision, and several reported rescinding offers after checking out Facebook." Yet college students' reaction to this fact suggests that they have a different understanding of privacy than potential employers: 42 percent thought it was a violation of privacy for employers to peruse their profiles, and "64 percent of students said employers should not consider Facebook profiles during the hiring process."

This is a quaintly Victorian notion of privacy, embracing the idea that individuals should be able to compartmentalize and parcel out parts of their personalities in different settings. It suggests that even behavior of a decidedly questionable or hypocritical bent (the Victorian patriarch who also cavorts with prostitutes, for example, or the straight-A business major who posts picture of himself funneling beer on his MySpace page) should be tolerated if appropriately segregated. But when one's darker side finds expression in a virtual space, privacy becomes more difficult and true compartmentalization nearly impossible; on the Internet, private misbehavior becomes public exhibitionism.

In many ways, the manners and mores that have already developed in the world of online social networking suggest that these sites promote gatherings of what psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton has called "protean selves." Named after Proteus, the Greek sea god of many forms, the protean self evinces "mockery and self-mockery, irony, absurdity, and humor." (Indeed, the University of Dayton survey found that "23 percent [of students] said they intentionally misrepresented themselves [on Facebook] to be funny or as a joke.") Also, Lifton argues, "the emotions of the protean self tend to be free-floating, not clearly tied to cause or target." So, too, with protean communities: "Not just individual emotions but communities as well may be free-floating," Lifton writes, "removed geographically and embraced temporarily and selectively, with no promise of permanence." This is precisely the appeal of online social networking. These sites make certain kinds of connections easier, but because they are governed not by geography or community mores but by personal whim, they free users from the responsibilities that tend to come with membership in a community. This fundamentally changes the tenor of the relationships that form there, something best observed in the way social networks treat friendship.

The New Taxonomy of Friendship

There is a Spanish proverb that warns, "Life without a friend is death without a witness." In the world of online social networking, the warning might be simpler: "Life without hundreds of online 'friends' is virtual death." On these sites, friendship is the stated raison d'être. "A place for friends," is the slogan of MySpace. Facebook is a "social utility that connects people with friends." Orkut describes itself as "an online community that connects people through a network of trusted friends." Friendster's name speaks for itself.

But "friendship" in these virtual spaces is thoroughly different from real-world friendship. In its traditional sense, friendship is a relationship which, broadly speaking, involves the sharing of mutual interests, reciprocity, trust, and the revelation of intimate details over time and within specific social (and cultural) contexts. Because friendship depends on mutual revelations that are concealed from the rest of the world, it can only flourish within the boundaries of privacy; the idea of public friendship is an oxymoron.

The hypertext link called "friendship" on social networking sites is very different: public, fluid, and promiscuous, yet oddly bureaucratized. Friendship on these sites focuses a great deal on collecting, managing, and ranking the people you know. Everything about MySpace, for example, is designed to encourage users to gather as many friends as possible, as though friendship were philately. If you are so unfortunate as to have but one MySpace friend, for example, your page reads: "You have 1 friends," along with a stretch of sad empty space where dozens of thumbnail photos of your acquaintances should appear.

This promotes a form of frantic friend procurement. As one young Facebook user with 800 friends told John Cassidy in The New Yorker, "I always find the competitive spirit in me wanting to up the number." An associate dean at Purdue University recently boasted to the Christian Science Monitor that since establishing a Facebook profile, he had collected more than 700 friends. The phrase universally found on MySpace is, "Thanks for the add!"—an acknowledgment by one user that another has added you to his list of friends. There are even services like FriendFlood.com that act as social networking pimps: for a fee, they will post messages on your page from an attractive person posing as your "friend." As the founder of one such service told the New York Times in February 2007, he wanted to "turn cyberlosers into social-networking magnets."

The structure of social networking sites also encourages the bureaucratization of friendship. Each site has its own terminology, but among the words that users employ most often is "managing." The Pew survey mentioned earlier found that "teens say social networking sites help them manage their friendships." There is something Orwellian about the management-speak on social networking sites: "Change My Top Friends," "View All of My Friends" and, for those times when our inner Stalins sense the need for a virtual purge, "Edit Friends." With a few mouse clicks one can elevate or downgrade (or entirely eliminate) a relationship.

To be sure, we all rank our friends, albeit in unspoken and intuitive ways. One friend might be a good companion for outings to movies or concerts; another might be someone with whom you socialize in professional settings; another might be the kind of person for whom you would drop everything if he needed help. But social networking sites allow us to rank our friends publicly. And not only can we publicize our own preferences in people, but we can also peruse the favorites among our other acquaintances. We can learn all about the friends of our friends—often without having ever met them in person.

Status-Seekers

Of course, it would be foolish to suggest that people are incapable of making distinctions between social networking "friends" and friends they see in the flesh. The use of the word "friend" on social networking sites is a dilution and a debasement, and surely no one with hundreds of MySpace or Facebook "friends" is so confused as to believe those are all real friendships. The impulse to collect as many "friends" as possible on a MySpace page is not an expression of the human need for companionship, but of a different need no less profound and pressing: the need for status. Unlike the painted portraits that members of the middle class in a bygone era would commission to signal their elite status once they rose in society, social networking websites allow us to create status—not merely to commemorate the achievement of it. There is a reason that most of the MySpace profiles of famous people are fakes, often created by fans: Celebrities don't need legions of MySpace friends to prove their importance. It's the rest of the population, seeking a form of parochial celebrity, that does.

But status-seeking has an ever-present partner: anxiety. Unlike a portrait, which, once finished and framed, hung tamely on the wall signaling one's status, maintaining status on MySpace or Facebook requires constant vigilance. As one 24-year-old wrote in a New York Times essay, "I am obsessed with testimonials and solicit them incessantly. They are the ultimate social currency, public declarations of the intimacy status of a relationship.... Every profile is a carefully planned media campaign."

The sites themselves were designed to encourage this. Describing the work of B.J. Fogg of Stanford University, who studies "persuasion strategies" used by social networking sites to increase participation, The New Scientist noted, "The secret is to tie the acquisition of friends, compliments and status—spoils that humans will work hard for—to activities that enhance the site." As Fogg told the magazine, "You offer someone a context for gaining status, and they are going to work for that status." Network theorist Albert-László Barabási notes that online connection follows the rule of "preferential attachment"—that is, "when choosing between two pages, one with twice as many links as the other, about twice as many people link to the more connected page." As a result, "while our individual choices are highly unpredictable, as a group we follow strict patterns." Our lemming-like pursuit of online status via the collection of hundreds of "friends" clearly follows this rule.

What, in the end, does this pursuit of virtual status mean for community and friendship? Writing in the 1980s in Habits of the Heart, sociologist Robert Bellah and his colleagues documented the movement away from close-knit, traditional communities, to "lifestyle enclaves" which were defined largely by "leisure and consumption." Perhaps today we have moved beyond lifestyle enclaves and into "personality enclaves" or "identity enclaves"—discrete virtual places in which we can be different (and sometimes contradictory) people, with different groups of like-minded, though ever-shifting, friends.

Beyond Networking

This past spring, Len Harmon, the director of the Fischer Policy and Cultural Institute at Nichols College in Dudley, Massachusetts, offered a new course about social networking. Nichols is a small school whose students come largely from Connecticut and Massachusetts; many of them are the first members of their families to attend college. "I noticed a lot of issues involved with social networking sites," Harmon told me when I asked him why he created the class. How have these sites been useful to Nichols students? "It has relieved some of the stress of transitions for them," he said. "When abrupt departures occur—their family moves or they have to leave friends behind—they can cope by keeping in touch more easily."

So perhaps we should praise social networking websites for streamlining friendship the way e-mail streamlined correspondence. In the nineteenth century, Emerson observed that "friendship requires more time than poor busy men can usually command." Now, technology has given us the freedom to tap into our network of friends when it is convenient for us. "It's a way of maintaining a friendship without having to make any effort whatsoever," as a recent graduate of Harvard explained to The New Yorker. And that ease admittedly makes it possible to stay in contact with a wider circle of offline acquaintances than might have been possible in the era before Facebook. Friends you haven't heard from in years, old buddies from elementary school, people you might have (should have?) fallen out of touch with—it is now easier than ever to reconnect to those people.

But what kind of connections are these? In his excellent book Friendship: An Exposé, Joseph Epstein praises the telephone and e-mail as technologies that have greatly facilitated friendship. He writes, "Proust once said he didn't much care for the analogy of a book to a friend. He thought a book was better than a friend, because you could shut it—and be shut of it—when you wished, which one can't always do with a friend." With e-mail and caller ID, Epstein enthuses, you can. But social networking sites (which Epstein says "speak to the vast loneliness in the world") have a different effect: they discourage "being shut of" people. On the contrary, they encourage users to check in frequently, "poke" friends, and post comments on others' pages. They favor interaction of greater quantity but less quality.

This constant connectivity concerns Len Harmon. "There is a sense of, 'if I'm not online or constantly texting or posting, then I'm missing something,'" he said of his students. "This is where I find the generational impact the greatest—not the use of the technology, but the overuse of the technology." It is unclear how the regular use of these sites will affect behavior over the long run—especially the behavior of children and young adults who are growing up with these tools. Almost no research has explored how virtual socializing affects children's development. What does a child weaned on Club Penguin learn about social interaction? How is an adolescent who spends her evenings managing her MySpace page different from a teenager who spends her night gossiping on the telephone to friends? Given that "people want to live their lives online," as the founder of one social networking site recently told Fast Company magazine, and they are beginning to do so at ever-younger ages, these questions are worth exploring.

The few studies that have emerged do not inspire confidence. Researcher Rob Nyland at Brigham Young University recently surveyed 184 users of social networking sites and found that heavy users "feel less socially involved with the community around them." He also found that "as individuals use social networking more for entertainment, their level of social involvement decreases." Another recent study conducted by communications professor Qingwen Dong and colleagues at the University of the Pacific found that "those who engaged in romantic communication over MySpace tend to have low levels of both emotional intelligence and self-esteem."

The implications of the narcissistic and exhibitionistic tendencies of social networkers also cry out for further consideration. There are opportunity costs when we spend so much time carefully grooming ourselves online. Given how much time we already devote to entertaining ourselves with technology, it is at least worth asking if the time we spend on social networking sites is well spent. In investing so much energy into improving how we present ourselves online, are we missing chances to genuinely improve ourselves?

We should also take note of the trend toward giving up face-to-face for virtual contact—and, in some cases, a preference for the latter. Today, many of our cultural, social, and political interactions take place through eminently convenient technological surrogates—Why go to the bank if you can use the ATM? Why browse in a bookstore when you can simply peruse the personalized selections Amazon.com has made for you? In the same vein, social networking sites are often convenient surrogates for offline friendship and community. In this context it is worth considering an observation that Stanley Milgram made in 1974, regarding his experiments with obedience: "The social psychology of this century reveals a major lesson," he wrote. "Often it is not so much the kind of person a man is as the kind of situation in which he finds himself that determines how he will act." To an increasing degree, we find and form our friendships and communities in the virtual world as well as the real world. These virtual networks greatly expand our opportunities to meet others, but they might also result in our valuing less the capacity for genuine connection. As the young woman writing in the Times admitted, "I consistently trade actual human contact for the more reliable high of smiles on MySpace, winks on Match.com, and pokes on Facebook." That she finds these online relationships more reliable is telling: it shows a desire to avoid the vulnerability and uncertainty that true friendship entails. Real intimacy requires risk—the risk of disapproval, of heartache, of being thought a fool. Social networking websites may make relationships more reliable, but whether those relationships can be humanly satisfying remains to be seen.

Christine Rosen is a senior editor of The New Atlantis and a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.

Christine Rosen, "Virtual Friendship and the New Narcissism," The New Atlantis, Number 17, Summer 2007, pp. 15-31.

Thursday, October 4, 2007

A Free Night of Amazing Music.

Paris Hilton on David Letterman

Sunday, August 19, 2007

Thursday, April 26, 2007

Los Desaparecidos at Museo Del Barrio

Feb 23 - June 17, 2007

I saw this exhibit today. "Los Desaparecidos". I really like political art, but this exhibit was a bit intense even for me. The security guard asked me if I was okay as I walked out of the exhibit. I don' t know if I looked upset, or if I was just pale after seeing all the installations. The exhibit was upsetting. One of the artists whose work really struck me was a Colombian artist by the name of Oscar Muñoz. The name of his piece was "Project for a Memorial" wherein there are 4 television screens with a separate video on each. They are videos of him sketching a man's face with water on a rock. As he drew some other feature of the same face, the other parts of the drawing dried and disappeared. It was so frustrating to watch it over and over again.

The photograph of the Rio de la Plata where the bodies of political dissidents were dumped after having been sedated was hard to look at - the river looked cold and unforgiving and yet that is how many people met their fate.

Another artist whose work struck me was Luis Camnitzer , and one photo in particular that read, "He was losing his will to clarify."New York, NY – January 30, 2007 –-El Museo del Barrio, New York’s premier Latino and Latin American cultural institution, will present The Disappeared (Los Desaparecidos) from February 23 – June 17, 2007. This traveling exhibition, organized by the North Dakota Museum of Art and curated by Laurel Reuter, brings together visual artists’ responses to the tens of thousands of persons who were kidnapped, tortured, killed and “vanished” in Latin America by repressive right-wing military dictatorships during the late-1950s to the 1980s.

The Disappeared (Los Desaparecidos) gathers 14 contemporary living artists from seven countries in Central and South America (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Guatemala, Uruguay and Venezuela), all of whose work contends with the horrors and violence stemming from the totalitarian regimes in each of their nations during the mid- to late-20 th century. Some of the artists worked in the resistance; some had parents or siblings who were disappeared; others were forced into exile. The youngest were born into the aftermath of those dictatorships. And still others have lived in countries maimed by endless civil war. These artists whose work is represented in the exhibition are Marcelo Brodsky , Luis Camnitzer , Arturo Duclos , Juan Manuel Echavarría , Antonio Frasconi , Nicolás Guagnini , Nelson Leirner, Sara Maneiro , Cildo Meireles , Oscar Muñoz , Ivan Navarro , Luis González Palma , Ana Tiscornia and Fernando Traverso . Also included is a collaborative installation Identity/Identidad by a collective of 13 Argentinean artists.

The range of visual languages -- drawings, prints, photographs, installations and mixed media -- incorporated in The Disappeared (Los Desaparecidos) frequently employs similar forms to evoke the presence of the missing person or persons. Bodies, faces, personal possessions and names, often methodically compiled and arranged, appear both boldly and subtly throughout the work in the exhibition. “Through their intense visual and emotional impact, these works communicate the unspeakable and reveal the artist’s assumed role of social responsibility towards ending the silence surrounding these extreme cases of human rights violations,” says Julián Zugazagoitia, Director of El Museo del Barrio. “In this context of public awareness and education through art, El Museo, as the only venue in the Eastern United States for this internationally traveling exhibition, aims to assemble as broad an audience as possible to confront and preserve the memory of these recent historical tragedies.”

Free public programs for adults, educators and children will be offered in relation to the exhibition and to encourage dialogue among viewers. Scheduled programming includes a series of film screenings, monthly family tours and workshops, an evening of music as a tribute to los desaparecidos in March, and an artist panel moderated by Columbia University Professor Andreas Huyssen on May 23. A bilingual illustrated color exhibition catalogue written by Laurel Reuter and Lawrence Weschler and produced by Charta , Italy with funding from The Lannan Foundation will accompany The Disappeared (Los Desaparecidos).

Support for this exhibition has been provided by the Otto Bremer Foundation, the Andy Warhol Foundation and the Lannan Foundation.

Major funding for the presentation of The Disappeared (Los Desaparecidos) at El Museo del Barrio provided by the Oak Foundation. Additional support provided by Mahnaz I. and Adam Bartos and by Open Society Institute.

About El Museo del Barrio

El Museo del Barrio is New York ’s premier Latino cultural institution, representing the diversity of art and culture in the Caribbean and Latin America . As one of the leading Latino and Latin American museums in the nation, El Museo continues to have a significant impact on the cultural life of New York City and is a major stop on Manhattan’s Museum Mile as well as a cornerstone of el barrio, the Spanish-speaking neighborhood that extends from 96 th Street to the Harlem River and from Fifth Avenue to the East River on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. El Museo was founded in 1969 by artist and educator Rafael Montañez Ortiz in response to the interest of Puerto Rican parents, educators, artists and activists in East Harlem who were concerned that their cultural experience was not being represented by New York ’s major museums. In 1994, corresponding to substantial local and national demographic changes, El Museo broadened its mission to present and preserve the art and culture of Puerto Ricans and all Latin American and Latino communities throughout the United States.

El Museo’s varied permanent collection of over 6,500 objects from the Caribbean and Latin America includes pre-Columbian Taíno artifacts, traditional arts, twentieth-century prints, drawings, paintings, sculptures and installations, as well as photography, documentary films and video. Through the sustained excellence of its collections, exhibitions, publications and bilingual public programming, El Museo reaches out to diverse audiences and serves as a bridge and catalyst between Latinos, their extraordinary cultural heritage, and the rich artistic offerings of New York City .

El Museo del Barrio is located at 1230 Fifth Avenue between 104th and 105th Streets and may be reached by subway: #6 to 103rd Street station at Lexington Avenue; #2, #3 to Central Park North/110 th Street station or by bus: M1, M3, M4 on Madison and Fifth Avenues to 104th Street; local crosstown service between Yorkville or East Harlem and the Upper West Side in Manhattan M96 and M106 or M2. Museum hours: Wednesday - Sunday, 11AM to 5PM . Closed on Monday and Tuesday. Suggested museum admission: $6 adults; $4 students and seniors; members and children under 12 accompanied by an adult enter free. To learn more about El Museo, please visit our website at www.elmuseo.org or call 212-831-7272.

Sunday, March 18, 2007

'Nemesis: The Last Days of the American Republic' - Chalmers Johnson

'Nemesis' Tells of U.S. in Peril

Monday, February 5, 2007

"México: el racismo que no se nombra"

A pesar de las evidencias abrumadoras, en nuestro país se sigue negando la existencia de prácticas de discriminación racial. El presidente puede hablar de los trabajos que ni los negros hacen y unos sindicalistas pintar suásticas en Paseo de la Reforma. Nada pasa. Quizá porque el racismo a la mexicana es, digamos, "más sutil" o porque el nuestro es un racismo sobre todo contra los indígenas y los morenos en general, un racismo de exclusión

Nadie en México admite ser racista, así como nadie quiere verse más oscuro de lo que un canon no dicho de aceptación social exige. Según el Consejo Nacional para prevenir la Discriminación (Conapred), 40% de los mexicanos está dispuesto a organizarse con otras personas para solicitar que no se establezca cerca de su comunidad un grupo de indígenas. Y es lógico, pues 43% opina que los indígenas tendrán siempre una limitación social por sus características raciales.

La declaración del presidente Vicente Fox sobre los trabajos que ni los negros quieren, declaración de la que nunca se retractó, demuestra el vergonzante racismo que todos padecemos.

¿Qué es el racismo para que la mayoría de las personas se sientan intimidadas frente a su sola mención? La Real Academia ofrece dos definiciones: "exacerbación del sentido racial de un grupo étnico, especialmente cuando convive con otros", la primera; y "doctrina antropológica o política basada en este sentimiento y que en ocasiones ha motivado la persecución de un grupo étnico considerado como inferior", la segunda. Dicho de esta forma, el racismo parecería algo casi limpio, libre de connotaciones económicas, de género o de acceso a los servicios públicos. Peor aún, una especie de locura o de fobia, individual o colectiva: una "enfermedad" de la que ninguna persona es plenamente responsable.

Por ello, una amiga en París pudo soltar durante una cena: "De Bush puede decirse cualquier cosa, menos que sea racista. Mira que nombrar a una mujer negra en la Secretaría de Estado...". Según ella no existe razón alguna para llamar racista a un presidente que redujo los fondos para la manutención de los diques de Nueva Orleáns: fue un mal cálculo económico que sería tendencioso relacionar con el hecho que la capital de Luisiana estaba habitada precisamente en 80% por población negra y pobre.

Las dos definiciones tampoco explican el racismo que no se nombra en México. No hay corriente o partido político que reivindique algún tipo de superioridad racial y la oficial definición de México como país mestizo acalla cualquier exaltación de un grupo étnico. No obstante, es indudable que los habitantes de los 62 pueblos indios y las minorías negra y asiática de México sufren discriminación, invisibilización, pauperización y difícil acceso a los servicios públicos como consecuencia de una discriminación racial tan difusa como negada.

Durante el Foro Regional de México y Centroamérica sobre Racismo, Discriminación e Intolerancia, que se llevó a cabo en la ciudad de México en noviembre de 2000, Ariel Dulitzky afirmó que la discriminación racial es negada en América Latina y que este afán por ocultar, tergiversar o encubrir el racismo dificulta las medidas efectivas que pueden tomarse en su contra. La igualdad, sea racial, de género, étnica, religiosa u económica, dista aún de ser vista en la región como un requisito esencial y fundacional de la democracia. Todo acto de racismo es, por lo tanto, negado "aquí no estamos en Europa donde queman a los migrantes", interpretado "decir que los indios no tienen cultura no es racismo, es que no tienen acceso a la escuela" o justificado "sí, se les metió a la cárcel, pero no entendíamos qué decían, no hablan español".

Los chistes, en México, ridiculizan todos los grupos raciales y étnicos que no sean el mayoritario o el de elite (blancos ricos), subrayando algunas de las características propias de su condición de marginados. Al mismo tiempo que no puede verse un solo comercial televisivo o cartel publicitario en el que aparezca un bebé o niño de rasgos indígenas, ser indio es sinónimo de ser inculto y portarse como ranchero es demostrar timidez o poco savoir faire; los negros se cenan entre sí y nadie puede diferenciar a un chino de otro. Todos los lugares comunes del racismo están comúnmente en nuestras bocas y no hay familia que no esgrima un abuelo español, una tía inglesa o un primo francés para subir de categoría social.

El mestizaje encubridor

Mestiza es la persona que nació de madre y padre con fenotipos distintos o pertenecientes a etnias de culturas diversas. En México y Centroamérica es la persona hija de europeo y amerindia, aparentemente sin preferencia hacia ninguna de sus raíces. No obstante, el mestizaje encubre una gran mentira, la de la armonía entre grupos étnicos y raciales gracias a la violencia sexual colonial, que sigue siendo cimiento de las jerarquías de género y de raza en la actualidad. De hecho, el papel de las mujeres indígenas y negras es rechazado en la formación de la cultura nacional; la desigualdad entre hombres y mujeres es erotizada; y la violencia sexual contra las amerindias y negras ha sido convertida en un romance, como en el caso de Cortés y la Malinche. Según la brasileña Ángela Gilliam, a este conjunto de prácticas culturales, a la vez sexistas y racistas, se le podría llamar en América "la gran teoría del esperma blanco en la formación nacional". Quizá por eso entre los mestizos ser güero es poder reivindicar un padre o bien creerse superior, hermoso y con derechos.

Al fin y al cabo, conquista, colonización y racismo han sido indisociables y la cultura colonialista no ha desaparecido con la independencia política. La violencia es hija de esta tríada que hambrea, mata y ofende por segregación.